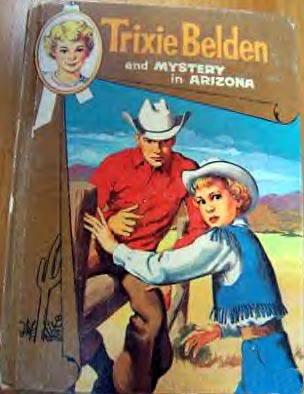

Series Spotlight Review: Trixie Belden: Native and American Identity in Julie Campbell’s Mystery in Arizona by Maia Adamina

Although there has been a welcome addition of more ethnic characters to the girls’ series canon, there just weren’t too many in the 50’s. If

they were included, it was usually in a very minor, and often, subservient role. However, in Julie Campbell’s

Trixie Belden and the Mystery in Arizona (1958), Hispanic and Native American characters are more fully developed and portrayed in a much more dignified manner than was

the norm.

Although there has been a welcome addition of more ethnic characters to the girls’ series canon, there just weren’t too many in the 50’s. If

they were included, it was usually in a very minor, and often, subservient role. However, in Julie Campbell’s

Trixie Belden and the Mystery in Arizona (1958), Hispanic and Native American characters are more fully developed and portrayed in a much more dignified manner than was

the norm.

The strong values Babs, Maria, and Rosita possess move them well beyond the stereotypes of laziness and violence which, unfortunately, were all too prevalent at the time. Campbell accomplishes this, basically, through portraying their cultures in a positive light. Additionally, she gives insight into the sometimes great divide between their native ethnicity and being American.

The first native character we’re introduced to is Babs, the full-blooded Apache

stewardess on the Bob-White’s flight from New York City to Tucson. A highly knowledgeable young woman, she translates native words and relays much of the background on Arizona that prepares for the dude ranch setting. As Trixie says, “she’s a walking geography and history combined” (50). She is so poised that Trixie, Honey, and Diana openly admire her. In fact, she is Diana’s acknowledged “very own ideal” (50).

It’s clear Babs is an independent young career woman who honors her cultural identity. Interestingly, she tells them her father, according to Apache tradition, supports her decision to have a career instead of getting married (65). In the past, careers weren’t an option for young unmarried native women, only spinsterhood or a husband. By having a career and staying true to her culture, Babs is a positive gateway for Tucson’s multiculturalism. She has successfully navigated the line between being a native and an American. She is both.

Like Babs, Maria, the cook at the ranch, is kind and knowledgeable. She teaches the boys -- Brian, Mart, and Jim -- how to cook her native Spanish dishes sharing her heritage as well as celebrating it. She is also similar to Babs in that she is a modern and americanized young woman – her English is sprinkled with Spanish, although, as Trixie notes, she speaks without an accent.

Unlike Babs, however, Maria is conflicted between her two cultures - Mexican and American. The description of the gigantic, sleekly modernized kitchen engulfing her emphasizes that: “The slim young Mexican woman who was working at one of the sinks seemed to be dwarfed by the appliances and fixtures” (107). Her response stresses her inner conflict -- a conflict that arises out of her reluctance to practice the old customs and her little boy’s need to: “I am used to this kitchen now, but it never fails to make me feel small” (107).

Maria’s in-laws are the family who has disappeared back to Mexico in order to celebrate a secret family tradition and she refuses to let them take her son, Petey. As Trixie observes, Maria “is so very Americanized that she almost – but not quite – makes fun of Mexican customs” (240). However, as Petey becomes increasingly distraught, Maria realizes she cannot deny her son’s Mexican heritage. After all, he is half hers, Americanized, and half her husband’s, of the old ways. Campbell places the weight of the decision directly on the conflicted Maria; her husband is dead and therefore cannot order her to let Petey go. Ultimately, Maria takes Petey to join the rest of the family in Mexico succumbing to family custom.

However, Maria’s decision to join her in-laws still leaves her conflict unresolved. She only goes in order to take Petey, not for herself but out of fear that Petey will somehow be harmed by her refusal to take him. After all, the boy tries to run away several times. Hence, she is caught between her desire to be modern and American and the need to honor the customs and heavy emphasis on family obligation that are fundamental to her Hispanic heritage.

Rosita, the young Navajo maid, is working at the ranch as a direct result of her

inner conflict between her American and Native ways. She is proud of her culture’s customs and understands their importance: “My father [ . . . ] is a long hair, but I am not ashamed of him because he does not go to the barber regularly as white men do” (236), and it is her lack of native jewelry that arouses Trixie’s suspicions.

However, we understand Rosita’s conflict with her dual identity when we learn she has encouraged her father, a silversmith, to use a modern tool to make his work easier. As a result, her father badly injured his hand, and instead of going to a doctor, he sees a medicine man. Her father can no longer work and the only thing that will save his hand is an operation and subsequent rehabilitation. Rosita leaves school in order to earn the money. This brings her no solace, however, as she has to break tradition by going behind her parents’ backs. As she says, “my parents would object very much” (98) to her working at the ranch. Rosita is obviously conflicted by guilt for trying to modernize her native father, and, like Maria’s in-laws the Orlandos, she feels “it is important to live up to the letter of old customs” (97).

As if to further emphasize how Rosita is torn between cultures, her characterization reflects both worlds. She is described as a beautiful Navajo girl in traditional dress whose English contains Navajo words. She, like Maria, also speaks without the trace of an accent (84). She wants to be a stewardess like Babs, but by leaving school she moves further away from that American dream. Her dilemma is ultimately solved by the Bob-Whites, who give her the money they’ve earned working on the ranch as a Christmas gift.

Campbell treats Babs, Maria, and Rosita with the utmost respect by not shying away from potentially problematic cultural issues. Instead, Campbell addresses them head on. For example, Babs remarks, smiling “without really smiling,” that “it is undoubtedly true that many of those [settlers] who did continue on to California were treated cruelly by my ancestors, but it is equally true that my ancestors were doing nothing more than trying to defend their own land” (47). Additionally, when a guest objects to being waited on by Diana and Honey, millionaires’ daughters, Mr. Wilson, the owner of the ranch points out that Isabella, the Mexican maid who returned to Mexico, “is a direct descendant of an Aztec noble.” He further points out that “Rosita’s grandfather was a great Navaho chief. He’s written up in all of the history books” (158). By alluding to the sometimes great divide engendered by an “us” and “them” mentality, Campbell highlights the very conflict each of these three young women come to terms with in their assimilation into American culture.

All in all, Babs, Maria, and Rosita each are shown in a positive light. Campbell insightfully gives voice to their pride in their respective cultures and to the conflict sometimes engendered between native ethnicity and being American. By developing their characters, and making Maria and Rosita central to the story’s mysteries, Campbell demonstrates her sensitivity to young women’s issues – all young women.

(I used the Cameo edition in preparing this article. -MA)

|

|

To sign up for a reminder-only(non-posting) service to remind you of when the latest issue is published online and when new ads are placed as well as any other important announcements, contests, etc., click on the following button:

Click to subscribe to TheSleuth